![[Photo: WIndswept point with pine trees.]](images/4KeyHbrPineTrees643x405.jpeg)

At the inlet of Key Harbour this point lies just inshore from the open water of Georgian Bay. The prevailing SW wind has bent these trees to leeward and stunted their windward branches.

The perfect weather continues and all the boats are running fine. We've left cottage country behind. The next leg is north through Indian Reserves and wilderness outposts, then west in open water until we reach Collins Inlet. Through that beautiful passage we continue on to Killarney. (Twelve Photographs)

| Date: | Tuesday, July 31, 2001 |

| Weather: | Warm. Deep blue sky and strong sunshine. |

| Winds: | Light from South |

| Waves: | Less than 1 foot |

| Departure: | Byng Inlet, Ontario |

| Destination: | Killarney, Ontario |

| Distance: | 60 miles by Small Craft Route |

Because of the rocking docks and long cable runs, it is much easier to get to the electricity up on the shore, so I move my coffee making operation from the noisy floating docks to a picnic table along the roadside. I brew a fresh pot and enjoy a little conversation with some passers-by, one a fellow boater who recounts good tales of cruising in Georgian Bay, the other just a local out for a morning walk. The weather continues fair and warm, with the skies clearer and more blue than any morning so far. This will be a beautiful day on the water. About 10:30 a.m. we are fueling at St. Amant's Marina Gas dock.

The fuel gauge shows we are just below 3/4-tank, and I am encouraged about the fuel consumption rate. Gas prices are actually lower here than down south, so I fill the tank to the brim. I have to add 127 liters of gas at $0.729-Canadian/liter before I can hear it whistling up the filler pipe. That converts to 33.8 gallons, $61-US total, and a bargain at $1.80-US/gallon. The knot-log says we have gone 55.3 miles on this segment of our trip. The fuel gauge now reads above the FULL mark, so we have refilled the tank to a higher level than it previously held. Fuel economy for this leg works out to a gloomy 1.6 MPG, but it must be better than that due to the variation in the fill levels. There must be room in the tank for about ten gallons beyond the "F" reading on the gauge, and allowing for that brings the fuel economy back to a more reasonable 2.3 MPG.

We lie off the fuel dock and drift in the current while the other boats also take on some gas for the next leg of the trip. The dark color in the river water is from all the old wood still on its bottom. In the early 1900's, the heyday of lumbering in this region, the second largest sawmill in Canada was located here, cutting timber at a prodigious rate and filling whole trainloads of railcars every few days with freshly sawn boards.

It is close to 11:00 a.m. by the time we reassemble our flotilla and motor slowly downstream to the Lake. We exit via the North Channel route, a shallower and less well-marked passage. The Small Craft Route proceeds northward, again in the shelter of the islands, and we pass the last cottage to be seen for many miles as we clear a rocky ledge at Cunningham's Channel (Mile 7 of Sheet 1 of Chart 2204).

The scenery takes on a noticeable change, the rock becoming even more rugged and the few trees canted and windblown. To make our passage more enjoyable, we have the fairest day of the trip so far. It is beautifully clear and the skies are a deep blue. We twist our course among the rocks, as always helped by the well-placed buoys and daymarks.

Around noon we take a brief diversion to look at the facilities in Key Harbour. We thought Byng Inlet was a bit rustic, but Key Harbour exceeds it in that quality. To describe Key Harbour you need to use words like "camp", "outpost", or "settlement."

At the mouth of the inlet an abandoned building and ruins of a long pier mark the entrance. The red brick and formal architectural style of the edifice easily identify it as an old railroad terminal. For a brief time around 1910, Key Harbour was the terminus of a shortline railroad that hauled ore down from Sudbury. From this now ruined pier it was loaded on ships and sent southward. After about a decade, the harbor's depth could not accommodate the newer, larger ships and the ore trade moved elsewhere. The direction of shipment reversed after that, and the railroad used the dock to receive coal hauled up from the south by ship and destined for use in those same Sudbury mines and their smelters.

The abandoned spur line runs north, but the long inlet runs straight due east and inland about 7 miles to the even smaller town of Key River, where the highway crosses the river. The controlling depth of this passage is charted as low as one foot, and even at the river bar there seems to be limited draft, especially this year. We leave the upstream waters of the Key River unexplored on this trip, and we return to the Small Craft Route.

![[Photo: WIndswept point with pine trees.]](images/4KeyHbrPineTrees643x405.jpeg) |

|

Windswept Shore At the inlet of Key Harbour this point lies just inshore from the open water of Georgian Bay. The prevailing SW wind has bent these trees to leeward and stunted their windward branches. |

After three days of heading north, our compass will swing westerly for the first time. We have reached the extreme northeast corner of Georgian Bay. At Mile 18 we divert from the main route and follow the old steamer track northward, into the maze of islands near Fox Island and through the tight passage at Dorés Run.

Everyone must have had a light breakfast because at 12:30 p.m. we stop for lunch and anchor just below Parting Channel on Obstacle Island. Don't you love the names of these places? (Obstacle Island-to-Gateway-Island detail on Sheet 2 of Chart 2204) We drop our hook and the other boats raft up to us, the light breeze from the southeast keeping us nicely taunt on our anchor rode. These rafted lunches become little picnics, as everyone passes a favorite dish or shares sandwich ingredients. A group of four small I/O bowriders cruises by headed south as we eat. They are the only other boats on the route today.

![[Photo: Anchoring for lunch in rocky cove.]](images/4LHGLunchPartingIs582x387.jpeg) |

|

Lunch at Obstacle Island I set the lunch hook in about 20-feet of water in the extreme northeastern reaches of Georgian Bay. This was one of the few times we anchored. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

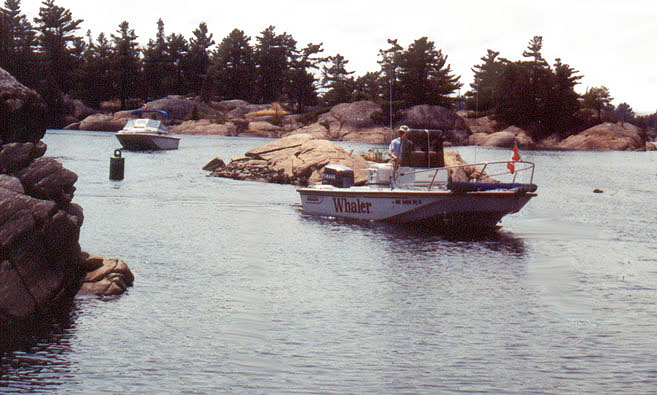

![[Photo: WHALE LURE eases thru Parting Channel.]](images/4JIMGPartingChannel609x366.jpeg) |

|

Parting Channel Larry Goltz guides WHALE LURE through the rocks at Parting Channel. Here we are on the old steamer track through the many islands of NE Georgian Bay, one of several of our diversions from the main course of the Small Craft Route. Photo Credit: Jim Gibson |

|

|

Parting Channel--Looking Back With WHALE LURE safely through, MEMORY enters the narrow pass. CONTINUOUSWAVE awaits her turn. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

![[Photo: Wide and deep channel among rocky islands, NE Georgian Bay.]](images/4JIMGNEGeoBayChan559x306.jpeg) |

|

Deep Channel The passage opens to a nice wide and deep channel. There are few signs of human development along these shores. In the distance CONTINUOUSWAVE is briefly the lead boat. Photo Credit: Jim Gibson |

After lunch and hauling the anchor, we resume our passage and face the challenge of Parting Channel, one of the narrowest points on the trip. It is no problem for our nimble Boston Whalers, although it might prove a bit more difficult if you were piloting a larger yacht.

In this section the channel runs through deeper cuts in rather tall islands, and we wind and twist our way among them. At 2:25 p.m. we reach the northernmost point in our journey as we enter the Main Outlet of the French River and turn southwesterly for a run down to the Bustard Island Lights and Georgian Bay (Mile 25 of Sheet 3 of Chart 2204).

For this next leg of the trip you want to pick a nice day, as there is no inshore passage available and you must traverse the northern extreme of the bay for about 15 miles in open water. If the wind is from the south, there is a hundred mile fetch and the waves can build to impressive heights by the time they roll up here. Today the breeze is moderate and the seas are running 1-2 feet from the southwest. It is not a bad passage, but after days of running in dead calm water it is definitely a change of pace for us.

To clear all the rocks and shoals, the Small Craft Route runs about three miles or more offshore, and it makes stingy use of buoys, which are several miles apart and generally cannot be seen from one another. From our starting point at buoy DJ, I know we are at the most southern point in the offshore passage, so I head due west and hope to pick up the next mark. Guided by his GPS and some previous waypoints, Larry (and Jim) head more offshore. I figure any mile to the south is one we'll just have to retrace, and I hold to a more inshore courseline, about 3/4-mile closer to the Ontario mainland shore.

After about six miles we are approaching easily seen Grondine Rock, a ten-foot high pinnacle with an unlighted daymark, but the 3-foot shoal on nearby Simpson Rock is nowhere to be seen. To solve this dilemma I turn on my handheld GPS for the first time in the trip and check our position. We alter course to approach Grondine Rock from due east, a safe bearing, and wait for the GPS to tell us we must be clear of Simpson Rock. In the process we get a close up look at Grondine Rock's shoreline.

There is something about seeing the color of the water change from indigo blue to a light creamy turquoise and watching the waves curl up and break on the shoals that gives rise to fear. This is not some subtlety of navigation learned after decades at sea, but a visceral reaction, something programmed into our DNA. We watch the elemental forces of wind and waves trying to push us onto the rocks, defeated only by the overcoming thrust of our propellers, and suddenly the air temperature seems colder, the water darker and more concealing, and our faith in the boat more in question. The lake does not seem as friendly and benign as it did a moment ago.

The twin outboard engines, mechanically ignorant of the closeness of the shoal, continue to run perfectly, and they power us past the hazard without missing a beat. By now our mates have rounded buoy DB2 a mile or so further offshore, and their course line turns northward to converge with ours. Soon we sight D84 and much larger D86, the sea buoy marking the inlet to Beaverstone Bay.

There has been a recent change in the entrance channel at Beaverstone Bay, and the one shown on my 1983-Edition chart is no longer used. Generally in this area there is little need for up-to-date charts. The terrain and lake bottom are all composed of rock that has not moved for millenia, and in some cases the hydrographic surveys themselves are almost 200 years old.

Motivated perhaps by economics and also good seamanship, the government has moved the entrance to Beaverstone Bay to an entirely new path. The old passage, with a limiting depth of about 7 feet, was a marvel of navigation, requiring four ranges and taking you within inches of rocks awash and 2-foot shoals. The new channel follows a much simpler route, needing only four buoys to mark the turns and maintains almost ten feet of water the entire way. We head downwind and enjoy a simple run into the protection of Beaverstone Bay. Suddenly we are back in the calm water of the Small Craft Route again.

(If you don't have the updated buoy positions, you can get them from another section of this website)

As we cruise rapidly up Beaverstone Bay's eastern shoreline, I notice my well-worn chart is filled with annotations of visits here in 1992, 1994 and 1997. (Mile 44 of Sheet 4 of Chart 2204) I recall those pleasant days of sailing with my children when they were still children, but both Chris and I wonder if we would be able to summon the energy needed to duplicate those live-aboard sailing marathons again.

Beaverstone Bay shoals as we proceed north and inward, eventually needing a dredged channel to connect us to our exit. Five sets of paired buoys guide us across the mud shoal. Then we turn west again, and enjoy the fabulous scenery of Collins Inlet.

Collins Inlet is not a river estuary, but a beautiful inland extension of Lake Huron which forms huge Phillip Edward Island. Its clear water runs at least nine feet deep along the 12-mile passage. In this section the shores are steep vertical clifts of cleanly cleaved rock which reveal massive upthrusts of layered granite. The sunlight filters through tall pine trees on the tops of the bluffs. The water is clear and free of hazards. You cannot find a nicer setting. After about five miles the passage opens and forms Mill Lake, with depths to 80 feet and more. We continue westward, exiting into an even narrower gorge-like waterway. Eventually the shoreline elevation drops, the water widens, and we return to the mouth of Collins Inlet and the final leg of our journey along Georgian Bay's eastern shore.

![[Photo: White quartzite cliffs of Collins Inlet]](images/4QuartziteShore702x491.jpeg) |

|

Beaverstone Bay We enjoy a quiet passage through many miles of beautiful quartzite shoreline in Beaverstone Bay. |

|

|

Collins Inlet Gorge Although it looks like a river, Collins Inlet is just a fortunate intrusion of Lake Huron far inland into the Ontario shore. The channel is clear and deep for miles. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

|

|

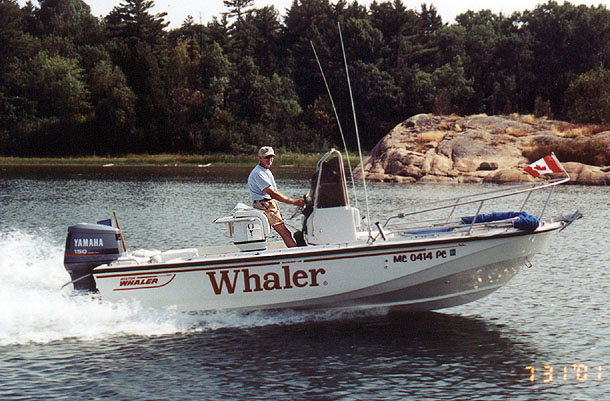

Smooth Ride In Smooth Water The 20-foot classic Whaler hull of our Revenge runs nicely at speed through the barely rippled water of Collins Inlet. With 140-HP our top speed is limited to about 32 MPH when fully loaded. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

|

|

Speeding Up As we get closer to Killarney (our destination), the speed picks up until finally we are running at 35 MPH or more. Technical note: the taller console and windshield of the Outrage-19 give the pilot good protection from wind and spray. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

|

|

Trim for Speed Our mini-cruiser trims up nicely on plane. We usually cruise around 22-24 MPH. The boat is just big enough to overnight on; it is just small enough to be easily trailered long distances. A fortunate geologic fault creates the nice scenery and the deep water. Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

(While stopped for a moment in Mill Lake, I inadvertently reset the knot log to zero. It had been indicating about 179 Miles travelled.)

As we head westward behind the shelter of One Tree Island, we again face open water. Our course line is a half mile offshore, and for some curious reason this stretch seems to be one of the roughest passages in the whole voyage. Perhaps the shoreline's shape or underwater contour is to blame, for it acts to reflect the waves back into the lake, where they add and subtract from the incoming rollers to form a nasty mixture. It is like sailing in a blender, as the curling water seem to come from all angles and strange standing waves exist in the middle of nowhere. The four mile run west-southwest to Killarney is a rough little trip, and we are extremely glad to round the lighthouse at Red Rock Point and enter the shelter of Killarney Channel.

It is about 6:30 p.m., rather late in the day for cruising boats to arrive at such a busy location as Killarney, and we pass a number of marinas which seem to be filled to capacity. At busy Sportsman Inn, however, they do have a small dock open which can accommodate our diminutive boats. We pull in and tie up, but we find the floating dock a little too small. It sits only a foot or so above the water, and our boats stick out several feet beyond the end of the pier. The narrow dock rocks back and forth, and fendering the boats is a problem. Next we discover that the entire marina facility shares a single bathroom and shower! There must be a hundred boats here, and even at 7 p.m. there is a line for the Men's room.

Larry pulls me aside and advises to delay registration for a minute; he's going to reconnoiter the facilities at the adjacent Gateway Marina and see what they have available. I take off to find Chris before she plunks the VISA card down for the night.

To our surprise, Gateway Marina has three fine slips available and brand new laundry, bathrooms, and showers, with a much lower boat-to-shower ratio. We cast off our lines and move 100 feet upstream to Gateway's docks for the night. Because of the low water, harbour master Fred personally directs each boat around the high spots inside the break wall and helps us into our slips.

| Marina: | Gateway Marina, 29 Channel Street, Killarney, ONT P0M 2A0, (705)287-2333 |

| Website: | none |

| Mooring: | Slip with finger piers. Floating docks. Rate = $1.25/foot |

| Dock height: | About two feet. |

| Bathroom: | 2 toilet/shower rooms. Very nice. Also laundry available. |

| Showers: | Total of 2. Excellent stall showers in individual bathrooms |

We moor CONTINUOUSWAVE on the up wind side of the dock, next to a similarly-sized, 2001-model cuddy cruiser from Ohio, powered by a big Mercury Optimax engine. There is a noisy family of four aboard, but I soon realize they're just using the dock for the day--they'll be heading back to their cottage in a few minutes. When the captain starts up the engine, it exhausts a huge plume of oil into the water, first noticed by the young boy on board, who points excitedly at the greenish sheen of oil flowing from the engine's lower unit. Having heard several horror stories regarding 2001 Mercury Optimax engines, we offer some counsel about keeping an eye on the engine and its performance. The Optimax powered cuddy-cabin departs, leaving me with an oily scum line deposit. The rest of my mates are fastidious boat keepers, so I have no choice but to immediately break out a long-handled brush and try to scrub the strange oil off the sides of my boat.

Dinner tonight we be even more casual than normal: fish and chip take out.

"They close at nine so we gotta go now," say Larry Goltz, who has picked up some local knowledge on our restaurant tonight.

![[Photo: Setting Canvas Up for the night.]](images/4LcgJimgCanvas446x404.jpeg) |

|

Daily Ritual Once docked, a daily ritual begins: putting up the canvas on the boats before setting out for dinner. Larry Goltz (LCG) and Jim Gibson are old hands at this chore. |

We walk a hundred yards down the waterfront to an old red school bus parked on a pier that houses Killarney's famous fish and chip carry out, HERBERTS FISH. I have been hearing about this place for years, with people telling me it's run by someone with the same last name as mine. It is a bit of a disappointment to finally get to the source and find that it is not HEBERT'S but HERBERTS.

When I get to the head of the line to place my order at the window, I mention to the folks in the hot and busy interior of the bus that I can't believe their name is Herbert instead of a good French-Canadian name like Hébert.

"No, it's 'Herbert'," says the nice woman in the school bus, as she hands me an enormous serving of fresh deep-fried whitefish with a ton of french fries. We sit down for dinner at a picnic table under an awning, enjoying the view on the waterway, the nice breeze blowing up the channel, and the warm golden glow of the sun declining in the northwest sky. Chris has thoughtfully brought me a cold BLUE reinforcement for the one I'm drinking in a plastic cup, so we have the perfect dinner.

After nine, with the window finally shut on the bus, the proprietors begin the process of closing up for the night, and I get a visit from one of them.

"I heard you mention 'Hebert' at the window," says a woman about my age, as I stretch my legs on the pier. "That used to be our name, but my dad changed it to Herbert."

"No kidding," I reply, now finally satisfied that I am getting the real story. "I didn't think there'd be a 'Herbert' up here. 'Hebert' is much more common in Canada."

"Yes, says my new-found distant cousin Ida, "if you go up to the cemetery you'll find grandfather's grave and it says HEBERT on it."

"I bet his name was Joseph, too?" I inquire.

"Right," she says a bit surprised, "Joseph Hebert."

"That," I tell her, "was my great-grandfather's name, too: 'Joseph Hebert.'"

From the genealogical research that I've done, it's the most common name for a male Hebert in eastern Canada. There are hundred of Joseph Hebert's in Ontario and surrounding areas going back many generations.

"We are probably cousins, fifth or sixth cousins, perhaps," I conclude.

"Originally grandpa was from Cheboygan, Michigan," she confides, "so if you want to do some more research, look around there.

Her dad changed the name to end years of misspellings and perhaps a bit of anti-French attitude in this predominantly Irish fishing village.

She spots my LABATT can and warns that I'll get her in trouble.

"Better get rid of that," she chides, "we're not licensed for beer."

I toss the can into the recycle barrel that supports a local charity. By the way, the fish at HERBERTS nee HEBERT'S is out of this world. If you ever get to Killarney, you have to try it. I'd put my name on it any day!

| Restaurant: | Herbert's Fish |

| Location: | Killarney, Ontario |

| Setting: | Red schoolbus on the pier |

| Ambience: | Outdoor Picnic table |

| Cuisine: | Deep Fried Fish Carry Out |

| Meal: | Best Fish and Chips on earth |

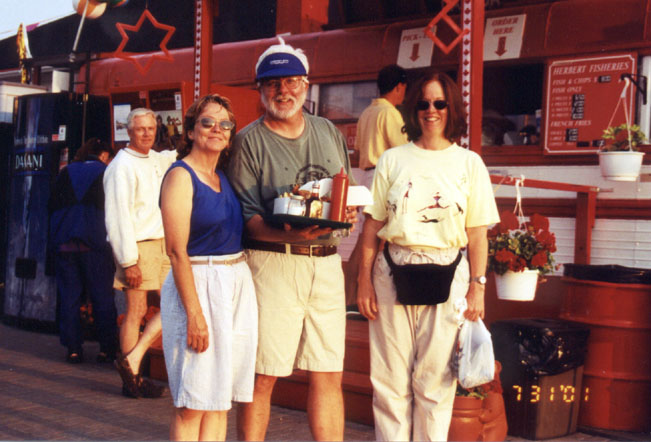

|

|

Long Lost Cousins I've just met Ida, who is probably a distant cousin. Her dad changed the spelling from HEBERT to HERBERT, adding to the confusion. The fish is great--don't miss it! Photo Credit: Larry Goltz |

The nine-day narrative continues in Day Five.

Copyright © 2001 by James W. Hebert. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited!

This is a verified HTML 4.0 document served to you from continuousWave

URI: http://continuouswave.com

Last modified:

Author: James W. Hebert

This article first appeared September, 2001.