continuousWave --> Whaler --> Reference

Original Design and Conception

of the 13-foot Whaler Hull

1958: Year of Boating Renaissance

Although I was only seven years old in 1958, even I could tell there

was something happening in the boating world. After a 21-year hiatus,

racing for the America's Cup was resumed. Wooden 12-meter yachts like

Columbia and Vim vied for the right to defend against the

British Sceptre. Monthly features in Yachting magazine

told all about the competition and preparations for it.

The Cup races were a good bellwether for the return to normalcy

in the American economy and lifestyle. The depression of the 1930's, the

World War of the 1940's, and the Korean conflict of the early 1950's were

finally behind us. American industry was finding

capacity and market for recreational products, after decades of producing

only industrial goods and war machines.

It was a time of innovation in many areas. Bell Labs announced

the invention of the transistor. Sputnik flew overhead. Space was

soon to be conquered. The American consumer was ready for something

new, something innovative, and for the first time in decades,

the American consumer had the money to buy it.

The post war years were good times economically, and there was spare

money and spare time for non-essentials like recreational boating.

Into this setting, now introduce two men: C. Raymond Hunt and

Richard T. Fisher.

Richard T. Fisher was a Harvard graduate (Class of 1936, a Philosophy major

and one of only three in his class)

who was running an electric relay company.

In the back of Dick Fisher's head were ideas for designing and

building small boats, especially light-weight boats built with balsa wood.

"[In 1943] I became interested in the possibility of using balsa wood to make

a very strong, very light rowboat," said Fisher. "I designed one

and went so far as to find balsa wood in sizes and quantities larger than

were being used for model airplanes. But I never went any further with it.

I realized that you'd have the problem, let's say, of an eight-foot

pram that would weight 35 pounds. It would be strong as hell except that

it would dent very easily."

Too busy with his company, the idea didn't get any further development.

C. Raymond Hunt was a naval architect and a friend of Fisher's. Ray Hunt's

career as a boat designer was blossoming.

He was drawing innovative boats, including a tender for use by America's Cup

yachts that would ultimately evolve into the famous off-shore racer Moppie,

the deep-vee boat that would become the progenitor of Bertram Yachts.

Moppie would go on to amazing victories in off-shore racing;

she would have an article written about her in Sports

Illustrated; she would make Ray Hunt famous.

Together these two would collaborate and design the Boston Whaler.

Hull Form Development

In 1954 Dick Fisher came across a press releases on a new product,

a foaming-in-place plastic called polyurethane foam. "Right away I thought

of it as synthetic balsa wood," he said. The similarity to balsa wood

triggered those old ideas for light-weight boats.

"I became interested in [the foam] as a possible boat building material

figuring you could make synthetic balsa wood out of it," said Fisher.

"And yet you could probably put a skin

on it that would make it very strong."

Fisher did indeed build a boat with the new foam and skin technique,

creating a small sailing dingy.

Inspired by the Alcort Sailfish, the boat had a squarish bow that gave

it more of the appearance of a inland lakes scow.

Fisher was quite excited by the boat and the construction technique,

so he showed it to his friend, Ray Hunt.

While Hunt was impressed with the boat, he thought (probably correctly)

that there was a limited market for a sailing dingy:

"They've been [building] the Sailfish for several years and they've built two

or three thousand and there's more outboards than that on Lake Winnepesaukee."

"Why not build outboard boats," he proposed.

Back in the 1920's a Nova Scotian named Hickman had designed a novel

boat called the Sea Sled. Unlike traditional boats, the Sea Sled had two

widely separated hulls or "runners" and was blunt bowed. In Hunt's view,

the Sea Sled had never been properly exploited. So his initial design for

Fisher was very similar to a Sea Sled.

Using epoxy and styrofoam, Fisher soon built a prototype of Hunt's design.

"It had two keels," said Fisher, "one inverted V [between the runners] and

an anti-skid, anti-trip chine." Powering it with a 15-hp outboard, Fisher

ran the boat all summer, thinking it "the greatest thing ever."

When rougher weather came in the fall, a flaw in the new design was revealed.

When under heavy load and plowing along below planning speeds, the middle

cavity in the hull forced air into the water as it rushed into the propeller.

This lead to propeller ventilation and rough running for the motor.

Fisher took his problem to the originator of the Sea Sled, Hickman himself,

but this consultation held little hope for improvement. Hickman was certain

the Sea Sled was the way to go and offered no modifications.

Fisher decided that they'd have to "put some stuff on the bottom to move that

airy water out the there." Development took place at his home, located on a tidal marsh. "We'd take the boat down and put fiberglass things on the bottom at nine o'clock in the morning. Then we would wait until the fiberglass cured and run the boat and find out it didn't work and bring it back and start over again. We'd get maybe three experiments done in one day."

As his experiments evolved, the prototype boat began to have a growing appendage down the center, filling the space between the two runners until it dropped down aft to become a slightly Vee-ed bottom. At some point, Fisher called Hunt to come over and see the modified prototype.

Hunt went back to the drawing board, and produced a new design which would

ultimately evolve into the 13-foot Whaler. The new hull had a third element

between the two runners, projecting down and ending with a nine-inch flat bottom

sole in the middle.

Fisher, confident that they were on the right track, built a second prototype,

this one finished well enough that it could serve as the plug for a production mold.

On sea trials, which consisted of running the new boat full throttle from

Cohasset, Massachusetts to New Bedford and back (a distance of 120 miles),

Fisher found a new flaw: the boat was "wetter than hell." "A lot wetter,"

he said, "than the other boat had been." It was the nine-inch wide sole

that was throwing all the water and would have to be changed.

But a female mold had already been constructed from the new prototype.

Instead of modifying the prototype hull and re-testing, Fisher was

so certain he had the right correction he modified the mold!

Material was added to transform the flat center section into a vee-bottom,

creating more or less of a "pointed keel" in Fisher's words.

From that mold in the fall of 1956 came the Boston Whaler 13 foot hull.

And since then the lines of the hull have remained virtually

unchanged. The boat that resulted had good stability and excellent load

carrying capacity, two attributes that were expected from the

hull form, but it also had unexpectedly good performance and handling in

rough weather conditions. And its light weight and shape

were easily driven by the comparatively low horsepower outboard

motors of the time. Remember, in 1958 a 25 horsepower outboard

was a big outboard. In total, it was a design breakthrough.

|

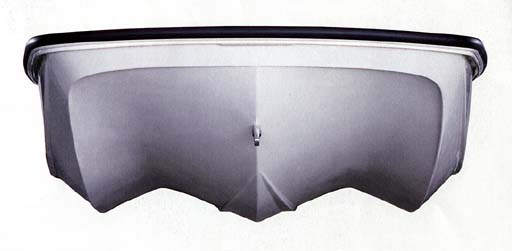

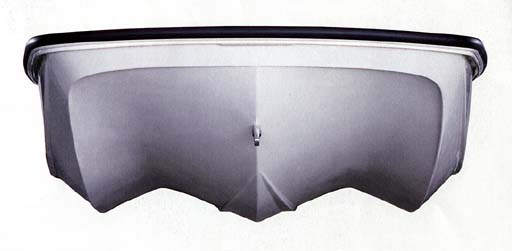

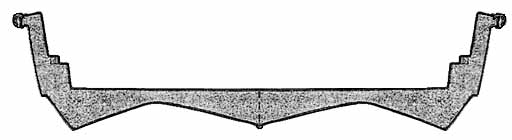

Head On View Whaler 13 Hull

The original Whaler hull evolved from the Hickman Sea Sled.

The two outer hulls are "runners". Fisher and Hunt evolved

the third central appendage to reduce "airy water" being

created by air trapped under the boat and flowing into the propeller.

This photo shows a more recent hull evolution.

The wrap-around bow chine--the "smirk"--was not in the original

molds.

|

Construction Technique

Dick Fisher's innovation wasn't just in the hull's underwater shape.

The construction technique was something totally new as well.

Fiberglass boats were gaining in popularity.

Up the coast in Rhode Island, Everett Pearson was about to make his famous

Pearson Triton sailboat, the first successful fiberglass sailboat

to be mass produced.

But Pearson's laminates were thick lay ups of resin and glass,

suitable for a heavy sailboat, but not applicable to a lightweight

outboard boat.

The Boston Whaler was unique in that it was essentially

made from foam, coated with a relatively thin skin of laminates and gelcoat.

The composite boat was strong, rigid, and light.

The foam provided unheard of floatation, too.

It made the hull very resistant to "oil canning",

and it worked to absorb sound as well.

At every turn, the foam filled hull seemed to have an advantage.

|

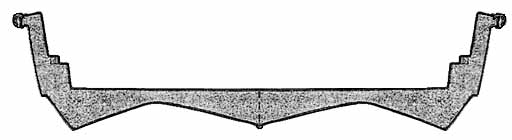

Cross Section Whaler Hull

The two molded forms, the hull and the liner,

join at the gunwales, where the rub rail conceals

their edges. The entire central volume of the boat

is filled with liquid foam, which expands and hardens,

bonding to the laminates and forming a unified

composite structure.

|

Whaler has never said much about its actual techniques for making the boat,

and well it might keep silent.

It seems that they are the only ones who have successfully mastered it.

What is known is that the boat consists of two conventional laminated skins,

the hull and the liner.

These are laid up at the same time using the usual female molds.

As the last layer of the laminate and resin is applied and curing,

the two sections are assembled into a single unit and clamped together while still wet.

The interior cavity thus formed is then filled with a liquid foam.

The liquid foam expands and hardens, filling every inch of the inner cavity

and at the same time completely bonding the hull and liner,

forming a single composite structure.

The conditions under which this is done are tightly controlled and

produce a superior product: the Boston Whaler.

Using a two-piece hull and liner allowed for other design innovations.

Although the hull had a complex shape, the interior could be made equally

sophisticated by molding it, too. First, a nice flat cockpit floor could

be created, providing an excellent surface for the boat's occupants to move

about. Into the deck a non-skid pattern could be molded, too. This would

improve traction and grip in wet conditions. Lockers, motorwells, and

seat supports could be created in the mold and not fabricated by hand

after the boat was assembled. By spending more time and money in

tooling of the molds, Whaler could save time and money in the

production process.

Even more revolutionary, the boat's extreme buoyancy (from its hull shape

and light weight) allowed the floor of the cockpit to be located above

the waterline! The meant that any water inside the boat could be easily

drained overboard through a strategically placed sump and drain in the rear

of the cockpit. You could leave the boat in the water at a dock or on a mooring

with the drain plug out and no water (from rain) would collect in the boat.

The boat's topsides were innovative, too. Instead of high freeboard and

tall gunwales, the boat was markedly low to the water.

Some might think this was a liability, but in fact it was an asset.

With the huge reserve buoyancy of the foam-filled hull,

the entire cockpit could be filled with water, yet the power head of the

outboard motor would still be above water!

The boat's engine could run and the boat could be manuevered while filled with water.

And, since the low freeboard meant there was less water trapped aboard,

the cockpit could be bailed or drained through the drain sump much faster

than on a boat with higher freeboard.

It was another revolutionary concept.

The low sides also made the boat very

easy to fish from, and easy to get back into from the water.

Those parts of the boat not made from fiberglass were top-quality as well.

The seats and consoles were beautiful mahogany with a glossy varnish.

All fittings were stainless steel. Railings were custom fit and welded.

Lifting eyes were over sized and through bolted for strength. Everything

about the boat was made first-tier quality.

Unfortunately, there was a price to pay for all of this. The foam itself

was quite expensive back then, five dollars a pound when five dollars was

enough to buy twenty five gallons of gas! And the high quality of the other

elements of the boat were costly, too. The result was a rather expensive

13-foot boat. Would it sell?

Marketing and Advertising

With all the features of the Boston Whaler, you'd think it would sell itself,

and it probably would have. But just to make sure it was a roaring success,

Dick Fisher ginned up some of the best promotional stunts ever seen in

the recreational boat business or anywhere else.

Like Apple Computer's legendary television commercial in the 1984 Super Bowl

that introduced the Macintosh computer to the world, Fisher created

an advertising gimmick that would instantly make Boston Whaler a household name.

To demonstrate the unsinkable nature of the boat, Fisher became the

star performer in a series of photographs that appeared in Life Magazine

in 1961. Casually seated in a tweed sport coat, bow tie, and hat,

Dick appeared completely bored and disinterested as a huge saw cut the 13-foot

Whaler hull in half. When the boat was in two pieces, he jauntily motored off in

the rear half. Advertising like this was enormously effective in getting

his fledgling company off the ground. The whole world read Life and

the whole world knew of the Boston Whaler.

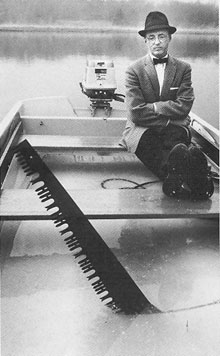

|

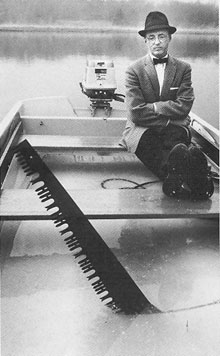

Life Magazine, May 19, 1961

Dick Fisher's marketing genius matched his engineering skills.

After this photo layout ran, the whole world knew the

Boston Whaler as the boat that was unsinkable.

|

Another famous ad photo showed Dick in similar attire, driving a Whaler up

a small rapids. The message was clear: the boat was indestructible. Reflecting

back on those early days, Dick said, "We knew it was a pretty good boat. And

when a kid in Cohasset stole one we knew right away it was going to be a success."

Even the name "Boston Whaler" was carefully chosen.

Fisher was looking for an "unstraight" name, something that people would remember.

The "whaler" idea came from the boat's ability to behave in following seas--

"A hell of a good thing for a Nantucket sleigh ride," said Fisher of the boat.

Of course, whaling dories are pointed on both ends and flat bottomed, while

the new hull was blunt ended and anything but flat bottomed.

More "unstraight-ness" for Fisher, which made "Whaler" good nomenclature.

Since the boat was made in the Boston area,

but Boston wasn't generally associated with Whaling, the "Boston Whaler"

name seemed to have just the contradiction in terms Fisher was looking for.

Summary

Thus in 1958 the Boston Whaler was born, designed with its unique hull shape,

constructed with new materials and techniques, and marketed with innovative

advertising and promotion. The timing was excellent, as interest in recreational

boating swelled among a new class of American boaters, enriched by a

strong post-war economy with the leisure time and the discretionary income to

enjoy a little yachting of their own.

Jim Hebert

February, 2000

Beverly Hills, Michigan

continuousWave --> Whaler --> Reference

DISCLAIMER: This information is believed to be accurate but there is no

guarantee. We do our best!

This article first appeared February, 2000.

Copyright © 2000 by James W. Hebert. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction prohibited.

This is a verified HTML 4.0 document served to you from continuousWave

URI: http://continuouswave.com

Last modified:

Author: James W. Hebert

Material attributed as quotations to Dick Fisher appeared originally in other sources, including a January 1978 MOTOR BOATING article by Marty Lurey as well as a number of in-house publications of the Boston Whaler company.