Many people have heard of the Great Lakes' most famous and relatively recent maritime casualty, the loss of the EDMUND FITZGERALD, which sank in a November storm in Lake Superior in 1975 and took with her all 29 crewmembers. The sinking of the FITZGERALD is often cited as the last major Great Lakes ship casualty with loss of life, but that designation overlooks the more recent loss of seven lives in a fire on the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL in June of 1979. Awareness of the FITZGERALD sinking was no doubt greatly increased by the popularity of the Gordon Lightfoot song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald." There is also a song about the fire on the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL, the excellent ballad "Fire on the Water," written by Charlie Maguire, but it is not as widely known. (Listen to an excerpt from the chorus of a version recorded by Lee Murdock.)

To increase awareness of the maritime casualty of the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL this article incorporates a reprint of another article that originally appeared in Proceeding of the Marine Safety Council, Vol, 38, No. 3, May 1981, a publication of the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Coast Guard. (Reference CG-129. The publication notes that "[s]pecial permission for re-publication, either in whole or in part, is not required provided credit is given to the Proceeding of the Marine Safety Council.") This technical article provides many details of the casualty and the circumstances under which it occurred. Perhaps this will help increase awareness of the Great Lakes's most recent major ship casualty with loss of life.

[ARTICLE REPRINT BEGINS]

Captain Norton is the Chief of the Marine Safety Division in the Ninth Coast Guard District, Cleveland, Ohio. The following article has been adapted from a paper he presented at the National Safety Congress in Chicago, Illinois, in October 1980.

The ancient Greek philosopher Thucydides is reported to have said that a collision at sea can ruin your entire day. While this certainly is true, a fire at sea can be a much worse experience with the most dire of consequences. The victims of a shipboard fire have limited resources with which to battle a conflagration and a very limited means of escape. In recognition of these perils, specific measures have been adopted which are intended to minimize the exposure of personnel to the perils of a fire and to provide reasonable and practical means of combating the fires that do occur.

Most regulatory efforts to date have been directed toward the "hardware" aspect of fire safety. This is exemplified by fire equipment regulations and the development of passive systems such as structural fire protection standards. Fire safety standards vary according to vessel flag, size, type, and date of build. Although the U.S. Coast Guard has long believed in the merits of structural fire protection, there are a number of older vessels which were built prior to the enactment of the newer standards and which are allowed to sail under the "grandfather" clauses of the regulations. This is especially common on the Great Lakes because of the life expectancy of fresh-water vessels. Therefore, wide variations in structural fire protection exist.

The human factor of fire protection at sea has not been addressed with the same emphasis that the hardware aspect has. This is not solely a Coast Guard responsibility but is rightfully shared with shipowners, operators, and licensed officers. The recent International Conference on Training and Certification of Seafarers conducted by the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization (lMCO) in 1978 recognized this by placing emphasis on the need to provide firefighting training courses. The development of the new Maritime Administration firefighting school in Toledo, Ohio, is an example of a response to this need.

The subject of this article is a tragic fire that occurred on board a Great Lakes bulk carrier and claimed seven lives. In this instance the vessel was of Canadian registry, and the fire occurred in U.S. navigable waters. The article is based on an analysis of the Coast Guard investigative report and the transcripts of the testimony from which the report was developed. The comments and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Coast Guard. The Coast Guard referred to in the text is the U.S. Coast Guard.

The vessel involved in the fire, the M/V CARTIERCLIFFE HALL, was built in Hamburg, Germany, in 1960 for service as an ocean ore carrier. In 1976 it was converted for use as a dry bulk carrier for Great Lakes service. After the conversion all accommodations and navigation spaces were located aft in a deckhouse five decks in height. The decks and deckhouse structure were steel. A steel bulkhead surrounded the machinery casing in way of the accommodations, and a steel bulkhead surrounded the galley. These steel internal bulkheads were intended to protect the accommodations from the higher fire risk areas of the engine room and galley. In retrospect, the isolation of the engine room from the accommodations worked in reverse and provided a measure of protection for the engine room watch personnel during the fire.

Structural fire protection was not utilized within the accommodations, nor were the accommodations fitted with either a fire detection or sprinkler system. For the most part, the internal subdivision of the accommodations, including the joiner paneling and false drop ceiling, were of wood construction.

The cabins on the poop deck level were fitted with windows in lieu of the airports fitted in the ship's side on the spar deck level. The airports and windows were to play a vital role in the casualty. In the forward end of the spar deck accommodations on the port side, one cabin, used in part as a workshop, was also used as a paint locker. The investigation revealed numerous cans of varying size in the ashes of that cabin. The ship was also fitted with two paint lockers protected by steel bulkheads, as well as fixed fire fighting systems, one aft and one forward.

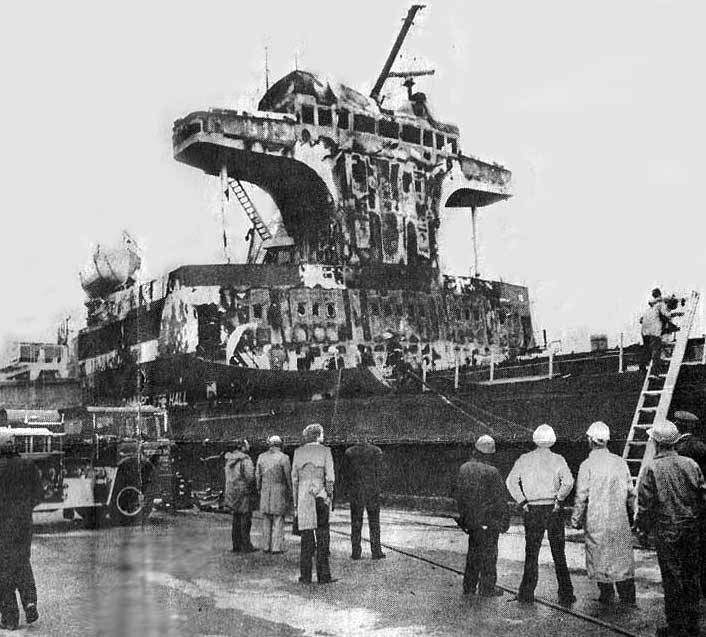

At mid watch relief time on June 5, 1979, as the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL headed across Lake Superior bound for Port Cartier, Quebec, the deckhouse was quite suddenly and totally involved in conflagration. Seven crewmembers lost their lives, six during the fire and one later as the result of burns. The entire deckhouse structure was gutted.

At 3:50 a.m. the morning watch mechanical assistant reported a fire in his cabin on the spar deck level. The watchman called the pilothouse and warned of the fire. The wheelsman sounded the general alarm, but the construction of the alarm switch was non-maintaining, and he had to continue to hold the switch in the closed position in order for the alarm to continue to sound. The mate on watch stopped the engine and attempted to call the master. In a matter of seconds smoke billowed up from the stairway leading below, and the pilothouse had to be evacuated. No "mayday" had been sent.

From that point on, the crewmembers, awakened by the warning and the general commotion, made various attempts to escape. A number of those sleeping on the spar deck level were turned back by the flames and smoke in the passageway and escaped through the airports in the ship's skin; they were then hauled to safety. Others were able to go through cabin windows; one hazarded the flames to get to the companionways. The two men on watch in the engine room escaped through a door in the stack casing that led to the boat deck.

By 4:15 a.m. the deckhouse was ablaze in its entirety, and the survivors had assembled on the spar deck forward of the deckhouse. Firefighting was commenced, but fighting the fire at this stage proved to be futile, and at 5:05 a.m. the crew, fearful of a fuel bunker explosion, abandoned ship. Seventeen crewmembers boarded the lifeboat and were rescued at 5:40 a.m. by the freighter THOMAS W. LAMONT. The watch standers from the engine room escaped in an inflatable liferaft and were rescued by the freighter LOUIS B. DEMERAIS. Six crewmembers were missing.

The fire eventually burned itself out, and the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL was later towed to Thunder Bay, Ontario. A subsequent search located the bodies of the six missing persons. Investigation also revealed that the engine room and fuel tanks did survive the fire with relatively minor damage. The accommodations spaces and navigation spaces, however, were completely destroyed.

How, in this age of sophisticated technology, such a sudden and tragic fire could occur is a very valid question. What combination of events transpired that resulted in a rapid and thorough conflagration of the deckhouse? A review of Coast Guard casualty data in general will soon reveal the overwhelming presence of the human factor in most casualties, whether it be direct and obvious or more subtle. The human factor as well as the hardware factor was present in either causing or contributing to this fire.

The Coast Guard investigation did not pinpoint the cause of the fire. However, it can readily be noted that two legs of the fire triangle—oxygen and combustibles—were present in abundance, waiting for the third, heat, to create the tragedy. It was determined that the fire most probably began in the port forward section of the spar deck accommodations. Whether the actual spark was caused by careless smoking, spontaneous combustion in the workshop, or possibly an electrical malfunction is irrelevant to the purpose of this article. Consideration must also be given to factors that contributed to the casualty in either an aggravating or a mitigating manner. The following comments describe several factors, most of which were contributory to this particular casualty but some of which more properly apply to fires at sea in general.

The deck house of the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL was not constructed with structural fire protection in mind. Within the false ceiling of the accommodations, a good deal of heat and fire spread could have occurred before the actual discovery of the problem. The suddenness of the conflagration subsequent to discovery supports this opinion. Recognizing the value of structural fire protection is akin to rediscovering the wheel. The presence of structural fire protection provides the opportunity to contain the fire to a small enough area so that people can escape. It also can contain the fire so that the fire fighting resources of the ship can effectively deal with the problem without becoming overwhelmed.

The Coast Guard recently published Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular No.6-80, dated April 2, 1980, a comprehensive guide that largely covers present knowledge of the subject.

The economics of present-day ship construction result in all accommodations being aft, sharing the deckhouse with the navigation spaces above. This creates a relatively high structure which also may become a chimney in the event of a fire below, thus exacerbating the problem. In this casualty, the fire on the lower deck level resulted in an almost immediate evacuation of the pilothouse. This occurred before the Master could be aroused, before a "mayday" could be sent, and before the general alarm had sounded for a lengthy period.

With all accommodations and navigation spaces aft, "all your eggs are in one basket." This type of construction makes it all the more important to protect the deckhouse so that the resources of communications, emergency equipment, clothing, etc., are not lost or rendered unreachable by a fire in the accommodations. Fortunately, in this instance the crew was able to reach and make use of the lifesaving equipment.

The accommodations of the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL were fitted with neither fire detection nor sprinkler systems. Although the Coast Guard places emphasis on structural fire protection, a fire detection and/or sprinkler system could have provided early warning and/or control of the problem.

Recently the Coast Guard published Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular No.7-80, dated April 2, 1980, which encourages the use of household-type fire detection equipment. While certain smoke or fire detectors of this type mayor may not be amenable to the stresses of the marine environment, they have the advantage of being an extremely small capital investment. In addition, on today's ships with their reduced manning levels, there are fewer human smoke and fire detectors on board. Electronic smoke or fire detectors could be most beneficial on some of the older U.S. Great Lakes vessels which have substantial amounts of wood in their structures.

Consideration should also be given to the fact that an individual's cabin, even though built of noncombustible materials, can support a smoldering fire in the bedding or furnishings. While the fire may not get out of control, the crewmember, if not warned, could easily be asphyxiated.

The two-man engineroom watch was protected down below by the steel bulkhead surrounding the engineroom casing where it passed through the accommodations. As a result of this protection, the fire in the accommodations caused relatively minor damage to the machinery spaces.

The fire within the accommodations prevented the activation of the CO system (which would have released CO2 to the engineroom), as the controls for the remote release could not be reached. In a wry twist of fate, this may have saved the lives of the two watchstanders, who could have been asphyxiated had the CO2 release been effected before they escaped.

The general alarm bell in the pilothouse had to be held in the depressed position in order for the alarm bells to continue to sound. As the pilothouse was evacuated very soon after the discovery of the fire, the bells also ceased to sound at that time. A maintaining switch would have continued the sounding of the general alarm until the fire's progress interrupted it.

The airports on the CARTlERCLIFFE HALL were of large diameter. That being the case, six crewmembers scrambled to safety when their normal escape route was blocked by smoke and flames. In addition, four other members of the crew escaped by climbing through their cabin windows. It is not unreasonable to conclude that the casualty toll would have been much higher had the vessel not been fitted in this manner.

The design arrangement of a ship should provide for two avenues of escape from the internal spaces. From the cabins of the CARTlERCLIFFE HALL the normal means of escape was to an interior passageway where one could go either left or right. The sudden conflagration precluded using this means of escape for most crewmembers, but fortunately ten of the crew made their way to safety through the unintended routes provided by the airports and windows.

The fire boundary of stairways and stairtowers should be maintained by doors between each deck level. These doors should not be hooked or chocked in the open position, nor should they be locked closed, since that creates a dead end.

Knowledge of a ship, including its escape routes, is a matter of prime importance. The frequent crew changes that are characteristic of seafaring today dictate a continuing need to indoctrinate new crewmembers. This includes ensuring that new crewmembers have a working knowledge of the ship's lifesaving and fire fighting equipment.

The engineroom watch of the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL was cut off from its normal avenue of escape during the fire. Fortunately the men knew the ship well enough to effect an escape through the stack casing onto the boat deck. This probably saved their lives.

Unfortunately crewmembers learn best how to handle themselves through participation in exactly what should be avoided, vessel casualties. As casualties should not be the norm, then, the training environment is most important. crewmembers should be trained to know exactly what their responsibilities are in emergency situations. Today's characteristic reduced manning levels increase the importance of the roles of the individual crewmembers if for no other reason than there are fewer crewmembers to draw from.

Emergency drills can be either meaningful evolutions or perfunctory performances. The latter accomplish nothing more than possible compliance with a regulatory requirement. The former can be an excellent training tool for all hands that will not only increase the proficiency of the crew in handling real problems but will point out shortcomings in the ship's organization as well. The value of emergency drills should correlate very positively with the effort that goes into them.

In the context intended here, good seamanship is closely akin to good housekeeping. This includes using spaces in a ship for their intended purpose, for example, keeping paint in a paint locker. It also includes reducing the hazards created by accumulations of trash and litter in rooms and service areas and the elimination of jury-rigged and unsafe electrical wiring. The list of possibilities is probably endless, but the matters addressed are well within the capabilities of the crew.

The safe operation of a ship depends not only on the safeguards of design and equipage that technology has provided but must lean very heavily on the human factor as well. Negative human factors such as indifference and apathy and the biggest problem—complacency—can defeat the best of design and equipment features.

The best structural fire protection can be defeated and rendered hazardous through improper action on the part of the humans involved. The worst of nonfire-safe construction can be significantly improved by positive action on the part of the humans involved. The optimum can be achieved only where the hardware factor and the human factor complement one another.

The purpose of this "visit" to a particular casualty was educational. The author hopes that the article proves thought-provoking in a positive manner; if so, it has achieved its purpose.

[ARTICLE REPRINT ENDS]

While the fire ended the lives of seven of the CARTIERCLIFFE HALL crew, it did not end the service life of the ship. The CARTIERCLIFFE HALL was repaired and continued in commercial service on the Great Lakes. In 2009, about 30-years after the fire, and by then named ALGONTARIO, the ship was retired from service and sold for scrap. A detailed account can be found at BOATNERD.COM and makes for further interesting reading, as it gives more details about the June 1979 fire. A scan of two newspaper articles from June 1979 also provides more information on the tragic fire.

Portions copyright © 2015 by James W. Hebert. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited!

This is a verified HTML 4.0 document served to you from continuousWave

URI: http://continuouswave.com/misc/cartiercliffehall.html

Last modified: Friday, 18-Sep-2015 14:31:29 EDT

Author: James W. Hebert

This article first appeared September 18, 2015.